PROKOFIEV

PROKOFIEVSergei Prokofiev (1891– 1953) was born in Sontsovka, a village in the Russian Empire that is now part of current-day Ukraine. He was introduced to music by his mother, and, demonstrating a strong aptitude for music, enrolled at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1904. There, he studied piano, conducting, and composition. After graduating in 1909, the young musician continued to hone his craft, ultimately showcasing in his compositions a unique brand of chromaticism. Living in the Russian Empire until its collapse in 1917, Prokofiev moved to San Francisco in 1918, Paris in 1920, and to the Bavarian region of Germany in 1922, only to return to Paris the following year. He continued to tour widely, including within the Soviet Union, eventually staying there for the last two decades of his life.

His compositional output spans the large-scale genres, including symphonies and suites, concertos for solo instruments and orchestra, operas, and ballets. Among his best-known works are Peter and the Wolf: Symphonic Tale for Children, which has been used for generations to introduce listeners to the instruments of the orchestra, and the three orchestral suites from which he created the music for the ballet Romeo and Juliet.

Prokofiev’s Concerto No. 2 in G minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 63 was premiered by Robert Soetens in 1935 with the Madrid Symphony Orchestra. The piece divides into three movements, which follow the traditional fast – slow – fast structure, and the orchestra personnel features pairs of each woodwind, horns, and trumpets along with strings and the solo violin. Of particular interest, however, is the percussion section, whose snare drum, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, and triangle evoke a sense of Spain, most notably in the third movement.

The first movement of the concerto, “Allegro moderato,” opens with the primary theme rendered by the solo violin alone. The theme is lyrical and tonally uncomplicated, but it defies expectations in a significant way, as the phrases are five beats in length and superimposed onto four-beat measures. The eight-bar theme suddenly gives way to more flourished and technical passages, but the theme remains constant, as it moves among the winds and orchestral strings over the course of 10 minutes. The solo violin part culminates in rich harmonies (produced by double, triple, and quadruple stops), and the movement comes to a harmonically satisfying, but stylistically surprising, finish.

The solo violin also opens the second movement, “Andante assai,” with a lyrical melody, which soars over distinctive and meticulously paced triplets in the clarinet and strings. The roles of these instruments are reversed as the movement is brought to a close, with the triplets in the solo violin juxtaposed against the duple melody in the strings. This type of rhythmic interplay is evident throughout the movement, lending a hint of jauntiness to an otherwise steady and measured piece.

The third movement “Allegro, ben marcato” is a dance that begins in triple meter, whose accent is on the first beat. The double, triple, and quadruple stops return in the solo violin, producing a twinge of chromaticism that adds the type of spice for which Prokofiev became well known. As the movement progresses, the meter changes as frequently as measure by measure. Sometimes, two beats are grouped in a measure, other times three. But the real excitement comes when Prokofiev creates combinations of five and seven beats, accentuated by the extensive percussion section. The melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic intensities build, bringing the piece to a dramatic end.

In the third movement of this piece, you will hear a percussionist play the castanets. The word “castanet” comes from castaña, which is Spanish for chestnut. This hand-held instrument is made of two chestnut-shaped pieces of slightly hollowed-out wood, which are secured to each other by string to form a clam shell. Performers typically use two castanets—one in each hand—to create more rhythmically complex patterns than a single castanet could make. Castanets have long been associated with Spanish dances, and their placement in this concerto undoubtedly contributed the success of its premiere in Madrid, Spain.

“Amy Marcy Cheney Beach, 1867–1944.” N.d. Photographic print. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZ62-56790. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004682089/

Amy Marcey Cheney Beach (1867 – 1944) was born in New Hampshire, and as a mere toddler, exhibited impressive musical talents. During childhood, she studied the piano and composition and even performed her own pieces publicly. When she married Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach in 1885, the couple agreed that she would limit her performing engagements and focus on composition, for which she became very well known in the greater Boston area and beyond. Her successes garnered respect among her contemporaries and earned her inclusion in an informal, but prestigious assemblage of composers known as the Second New England School.

The Boston Symphony premiered her Symphony in E minor, Op. 32 (Gaelic Symphony) in 1896 to rave reviews, and with this concert, Beach became the first woman to have a work performed by the orchestra.

The instrumentation includes 2 flutes (+ piccolo), 2 oboes (+English horn), 2 clarinets (+bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, and strings. Throughout the piece, Beach makes references to various Irish tunes and, in one instance, her own composition.

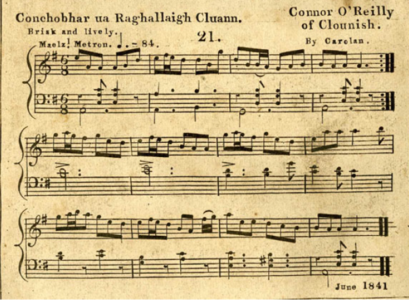

The first movement, “Allegro con fuoco,” opens with a chromatic ascent and horn call. With its tempestuousness, the music reflects sonically the concepts conveyed by the lyrics of Beach’s song “Dark is the Night.” These emotive passages are subsequently replaced by a lively jig, which is a traditional Irish dance. This jig incorporates the tune from the song “Conchobhar ua Raghallaigh Cluann” (“Connor O’Reilly of Clounish.”) Listen for the oboe to introduce the tune, then pay attention to the flute, who “answers” the oboe, but in a way that might seem “out of sync.” The mood of this movement changes regularly, creating the sense of distinct sections. Consider the extent to which certain features are repeated or referenced in later iterations. Note also the exchanges between the winds and strings and the ways in which they convey “Irishness.”

Like its symphonic contemporaries, Beach’s symphony has four movements. However, she has inverted the characters typically embodied by the second and third movements, whereby her second movement contains a dance and her third movement is slower and lyrical, rather than the other way around.

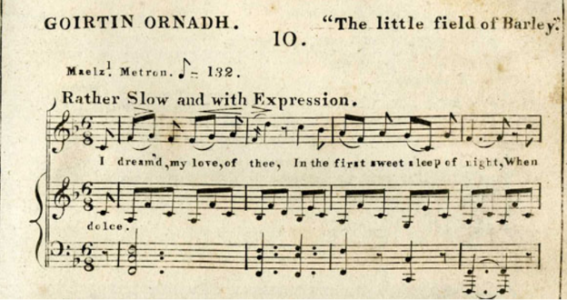

The opening section (of three) in the second movement is marked “Alla siciliana,” which refers to a dance of the same name, the siciliana. Typically, this dance conveys as sense of pastoralism, evidenced here by the use of horns and double reeds to signify shepherds. The movement opens with the French horn and strings, who hint at the siciliana, but it is the oboe that gives the first full iteration of the dance, with its characteristic dotted rhythm and subsequent triplet. Here, the tune “Goirtin Ornadh” (“The little field of Barley”) is set to the distinctive rhythm, but the melodic contour of Beach’s siciliana remains faithful to the original tune. Joined by pairs of clarinets and bassoons, and then a flute and French horns, the siciliana is rendered without strings. The movement changes character when the strings reenter at “Allegro vivace,” and snippets of the siciliana rhythm are juxtaposed with strong syncopation under running sixteenth notes. In the last section of the movement, “Andante,” the full siciliana returns in the English horn, rounding out the bucolic ambiance, but a flashback to the quick runs and syncopation close the movement.

The third movement, “Lento con molto espressione,” places a spotlight on an auxiliary instrument of the clarinet family—the bass clarinet. Through a series of solos—bass clarinet, violin, and cello—the somber mood is set. The oboe enters with the second half of “Paisdin Fuinne” (“The Good Child.”)

The third movement, “Lento con molto espressione,” places a spotlight on an auxiliary instrument of the clarinet family—the bass clarinet. Through a series of solos—bass clarinet, violin, and cello—the somber mood is set. The oboe enters with the second half of “Paisdin Fuinne” (“The Good Child.”)

The opening part to another Irish tune, “Cia an Bealach a Deachaidh Si” (“Which way did she go?”) is rendered first by a violin and then a flute. The second half of the tune appears later, and Beach alternates these tune parts in her orchestral writing. As the movement concludes, the bass clarinet returns with its simple, but expressive melody, which is dovetailed by the solo violin and quietly completed.

The final movement of Beach’s symphony, “Allegro di molto,” employs a definitive theme, but it has not been attributed to a specific tune. Like the previous movement, this one has more than one character—with moments of propulsion juxtaposed with specific moments of reprieve.

[George Gershwin, 1898-1937, half-length portrait, standing, facing left].” N.d. Photographic print. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZ62-60866. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005678096/

George Gershwin (1898 – 1937) was born in New York City to parents who had immigrated separately from the Russian Empire. He studied piano in his youth, and by the time he was a teenager, he was gainfully employed as a musician—first as a song plugger on Tin Pan Alley and then as an arranger.

Listen to Musical Exaples from Tim Pan Alley

Despite his relatively short life, Gershwin composed important pieces that would redefine so-called “classical” music in the United States. His operas, Blue Monday and Porgy and Bess, infused jazz idioms and American references into the otherwise European construct. His orchestral pieces also showcased a variety of rhythms, timbres, and styles, which tapped into the wider impulses of modernism but, at the same time, stretched the musical imagination in new and unexpected ways. In the more popular musical realm, he composed several Broadway musicals and music for films, many of which were in partnership with his older brother Ira.

It is important to note that Gershwin’s compositional output spanned the timeframe also occupied by the flowerings of the Harlem Renaissance (WWI to mid-1930s) and its counterpart of the Midwest, the Chicago Renaissance (1933 to ca. 1950), during which African-American composers, such as William Grant Still, R. Nathaniel Dett, William Levi Dawson, and Florence Price made inroads in the classical music scene. They, too, included instruments, melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and other musical devices from non-European cultures (e.g., African and African-American) into classical music forms.

Cuban Overture was composed in 1932 after Gershwin had traveled to Cuba in the winter of that year. He originally titled the piece “Rumba,” which refers to the popular music-and-dance genre of the same name and to which he had been exposed while on his trip. A defining feature of the rumba is the presence of the claves (two sticks, which when hit, produce a clicking sound that can be heard over a large ensemble). The piece is constructed in a single movement, but it has three distinct sections. It is scored for three flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, and two bassoons (in addition to their auxiliary instruments: the third flute doubles on piccolo, English horn, bass clarinet, and contrabassoon), four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (including the xylophone, cymbals, wood block, “Cuban sticks” [claves], gourd, maracas, and bongos) and strings. Given the extensive percussion section, the piece was designed evoke the soundscape of Cuba, which is known for its ensembles of membranophones (drums made with skins [membranes] stretched over gourds, barrels, etc.) and idiophones (instruments made wood, metal, and the like, which strike each other or rattle against each other).

The first and third sections of Cuban Overture are fast, and the rhythmic pulses keep up an exciting momentum. The theme comes from “Échale Salsita,” a work created by the Cuban rumba star Ignacio Piñero, who had met Gershwin during the latter’s time in Cuba. The second section, which is slower and more sensual, features sonorous melodies in the woodwinds.

The clave rhythm is one of several types of five-unit rhythms known as “cinquillo” rhythms.

In the first and third movements, you will hear the following clave rhythm. You’ll also feel a sense of three, unequal beats instead of four equal ones, which yield an overarching syncopated sway in each measure. This is known as the “tresillo” rhythm, and Gershwin applies it on a broader scale within the orchestra, but he restricts the clave rhythm to the percussion.

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.