Welcome to the 40th Anniversary Season of National Philharmonic! Last year, NatPhil and the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center formed a partnership to make cultural arts experiences more approachable and accessible. I’m estatic to continue this partnership and serve as your musicological guide in this new season.

Throughout the season, we will explore how pieces of classical music intersect with other forms of expressive culture.

Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape and circumstances. To do that, I will introduce a number of archival resources held at the American Folklife Center, which will help us to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them.

We will dive into the archives, hone our research skills, share our findings, and address any lingering questions. But we’ll have fun, too, as we strengthen our listening skills and enhance your concert experience.

I assure you, regardless of your previous musical experiences or training, the partnership between National Philharmonic and American Folklife Center offers all of us the opportunity to learn – together.

Join me this 40th season of National Philharmonic!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

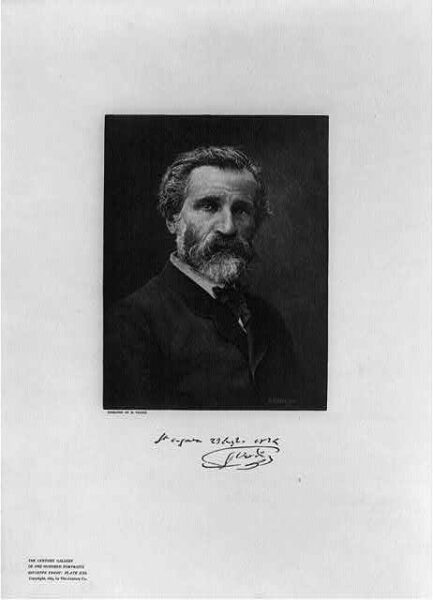

Velton, H., engraver. Guiseppe Verdi. 1885. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ 2002710412/

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) was born in northern Italy and showed great musical aptitude as a young boy, becoming an accomplished organist in his youth and a prolific composer while still a teenager. He went on to enjoy a long compositional career and focused his efforts on large-scale works that combined vocal and instrumental forces—most notably, over two dozen operas. Today, Verdi’s legacy remains as strong as ever, considering his collective operatic output receives more performances each year than that of any other composer. Some of his operas, such as Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata, and Aida have become household names, and selected arias, such “La Donna è mobile” from Rigoletto, have been popularized by their presence on television and film and are recognized by listeners worldwide.

The same holds true for his Messa da Requiem, which received its premiere 150 years ago, in 1874. Scored for four vocal soloists, chorus, and orchestra, this Mass for the dead was originally conceived by Verdi in memory of his esteemed predecessor and fellow Italian opera composer, Gioachino Rossini (1792 – 1868), but it was ultimately dedicated to writer Alessandro Manzoni (1785 – 1873.) Verdi’s Requiem, as it is commonly known, exhibits the same characteristics as one would expect of his operas—especially the soaring melodies among the soloists, the homophony of the large chorus (by which each choral line sings the same rhythm simultaneously), and the exceptionally colorful timbres offered by the orchestra, which is populated by extra wind instruments.

The Requiem’s woodwind section contains 3 flutes (with the third doubling on the piccolo), pairs of oboes and clarinets, and 4 bassoons. Originally, Verdi’s brass section comprised the traditional 4 horns and 3 trombones, but 8 trumpets (4 of which are offstage) and an ophicleide, which is now obsolete and replaced by a tuba. But, during its prime of the nineteenth century, this brass instrument, which came in a variety of sizes, appeared in significant orchestral pieces, such as French composer Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique (1830), even though it was never considered a standard orchestral instrument.

In the final movement of Berlioz’s five-movement instrumental work for orchestra, the ophicleide carries the ominous Dies irae tune, which the composer inserted to symbolize the funeral of the artist whose life is depicted in this work. Indeed, the term “dies irae,” which translates from Latin as “day of wrath,” is synonymous with the concept of death. Dating from the thirteenth century (possibly earlier), Dies irae is a lengthy poem found in the Roman Missal, which is the book that contains texts, chants, and prayers required for the celebration of the Catholic Mass.

The first eight notes of this tune are among the most quoted in classical music, and can be heard in pieces by Joseph Haydn, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Franz Liszt, and others. But Verdi eschewed this tune, emphasizing instead the text of Dies irae and situating it within his larger musical rendering of the Requiem Mass.

The resultant seven-movement work reflects Verdi’s compositional prowess, and was, for some time, considered a bit too dramatic—that is, operatic—for a Requiem Mass. Nevertheless, as you follow along with the text, you’ll note that Verdi incorporates:

Each movement is distinguished from the next by its unique combination of text, timbres, and textures. Listen carefully to the obvious (and not so obvious) interplay between the vocalists and the orchestra, noting the extent to which the chorus exhibits dexterity and range.

For example, in Movement 1 (Introit), the chorus offers the opening prayer of the Requiem Mass

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, Grant them rest eternal, Lord,

et lux perpetua luceat eis. and may perpetual light shine on them

with the solemnity and hushed tones expected for such an occasion. In contrast, in Movement 2, the chorus returns with great ferocity and intensity to warn about the Day of Wrath.

This recurring section of Dies irae—punctuated by alternating strikes of the timpani and bass drum—is juxtaposed against the more reflective vocal lines of the soloists, including “Quid sum miser,” “Recordare,” and “Ingemisco.” As the vocalists soar, be mindful of the exquisite instrumental countermelodies—such as that of the bassoon in “Quid sum miser,” and that of the flutes in Movement 5 (“Agnus dei.”) You will also hear pronounced instrumental interludes, such as the brass fanfare that immediately precedes “Tuba mirum” (part of Movement 2) and another that opens Movement 4 (“Sanctus”). With Movement 6 (“Lux Aeterna”), a request is placed for “eternal light” and “eternal rest,” which aptly concludes with open chords in the bassoons, horns, and strings and the flute’s solo ascent to its highest register. The serenity of “Lux Aeterna” is challenged in Movement 7 (“Libera me,”) which recalls the ominous Dies irae and measured pace of the chorus’s homophony, while showcasing Verdi’s fugal writing by which different choral lines enter at different times with the same text. This movement functions as a grand finale, but in its last moments, the soprano, chorus, and orchestra return to peaceful sounds of the opening movement, drawing Messa da Requiem to a close with the phrase “Libera me,” which translates to “Deliver Me.”

If you’ve enjoyed National Philharmonic and Cantate’s performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, consider using the resources at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center to learn more about the ways Italian and Italian American culture continues to flourish. Then, broaden your opera knowledge by consulting a variety of resources held throughout the Library of Congress.

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.