Over the course of the season, we will explore how each of the pieces operates at the intersection of classical and folk musics. In each instance, we will start with a classical construct–that is, a concerto, a symphony, a solo piano piece, and the like–and we will investigate how and to what extent folk idioms are infused into each construct. Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape comprising all the musics with which he or she was familiar. To do that, I will introduce a number of primary (archival) resources that can be used to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them beyond what has been the subject of musical biographies and histories. Many of these primary resources are available at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, but I will include others to facilitate our efforts. Some of them can be consulted online, while others may be used onsite at the Library. But all of them, singly and collectively, document the variety of cultural expressions and lived experiences that have been, in some way, referenced by the composers in their works.

On this site, you will find links to manuscripts, unique images, archival repositories and their finding aids, sound recordings, and more. Explore as much as your time permits. Start with the four “quantitative interrogatives”: who? what? when? where?

Use these questions to guide your examination of the resources, individually and in combination with each other. Then, leverage your new (or nuanced) understanding of a particular folk idiom–a dance, a concept, a tune, a rhythm–to expand your knowledge of the piece in which this idiom appears.

Before and after each concert, we will have opportunities to discover new resources, hone our research skills, discuss our findings, and address any lingering questions. With each exchange of ideas comes the opportunity for discovery. May this be the beginning of an exciting musical journey—for all of us!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) was born in Halle (Germany), where he studied several instruments (oboe, violin, organ, and harpsichord) and learned to compose. After a series of professional appointments, Handel relocated in 1712 to London and flourished as a composer of anthems, operas, oratorios, and instrumental works. Through his musical endeavors, including the establishment of the Royal Academy of Music, Handel maintained important connections with members of the Royal Family and other influential figures of the day, enjoying their commissions and patronage.

Handel composed his most enduring oratorio, Messiah, in 1741, by which time he had already written approximately forty operas (or musical dramas). Oratorios are large-scale works for orchestra and chorus, typically with a religious theme. Unlike operas, the vocalists in oratorios do not appear “in character,” although some vocalists may be featured in solo arias, duets, and the like. Oratorios are not staged—that is, there is no scenery and no action.

For Messiah, Handel set a text written by his friend and collaborator, Charles Jennens (1700-1773). Although it is largely recognized today as Christmas music, the three-part, English-language oratorio tells the story of Jesus’s birth, death, and resurrection, thereby embracing more than liturgical seasons of Advent and Christmas. In fact, it was premiered in 1742 during the season of Lent.

Handel originally scored the piece for orchestra (2 trumpets, strings, continuo, timpani) and vocalists, but subsequent editions have enhanced the orchestra to include double reeds (oboe, bassoon) and horns. At the time, it would have been customary for double reeds (oboe and bassoon) to complement musical lines in the same range. For example, the bassoon would have been a part of the continuo, which, for Handel, usually included a small organ and harpsichord (sometimes two).

Messiah contains fifty-three “movements,” which are divided unequally among the three parts, which are described in the score as follows:

Of the fifty–three movements, only two are purely instrumental, including the very first one. Labeled “sinfony,” it functions as an overature to the entire work by setting the mood. With the exception of the second instrumental movement, each of the others features texts drawn from the King James Version of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, both of which were in use by the Church of England during the mid-eighteenth century. In Part One of his Messiah libretto, Jennens incorporated passages from the books of Isaiah, Haggai, Malachi, Matthew, Luke, and Zechariah. Part Two includes passages from the books of John, Isaiah, Psalms, Lamentations, Hebrews, and Romans. The final scene of Part Two, Scene 7, concludes with the famous “Hallelujah” chorus, whose text is derived from the book of Revelation. Part Three incorporates texts from the books of Job, 1 Corinthians, Romans, and Revelation.

Following the premiere of Messiah, Handel issued various changes to his score, including new settings of arias for the talented castrato Gaetano Guadagni. By the early 1750s, however, the score was relatively fixed, and it was programmed annually by Handel at the Covent Garden Theatre during the season of Lent.

It would not be until 1818 when the oratorio became associated with Advent and Christmas Day. That year, the newly formed Handel and Haydn Society of Boston gave the American premiere of Messiah on December 25—Christmas Day—and a new holiday tradition appears to have been born. Over the course of the twentieth century, Handel’s oratorio found its way into popular American culture, with excerpts from the Hallelujah chorus heard in holiday-themed movies, television shows, commericals, and more. These excerpts were, and still are, among the most widely recognized of all classical music.

But, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, scholars began to interrogate the culture of patronage, which had enabled Handel and his artistic contemporaries to thrive during their own lifetimes. In 2000, music librarian David Hunter published the article “Patronizing Handel, Inventing Audiences: The Intersections of Class, Money, Music, and History,” in which he explored the dependence of creators in eighteenth-century Europe on their financial supporters—their patrons. As he continued conducting research on Handel, Hunter discovered that one of Handel’s patrons, James Bridges (the Duke of Chandos) had been an investor in the Royal African Company, which was the official slave trading company of England. According to various company ledgers, Handel had also bought and sold Royal African Company stock. In a more recent article “Handel Manuscripts and the Profits of Slavery: The ‘Granville’ Collection at the British Library and the First Performing Score of Messiah Reconsidered” (2019), Hunter retraces the ownership history of Messiah’s first performing score and argues that it was “purchased in part thanks to profits derived from the slave economy.”

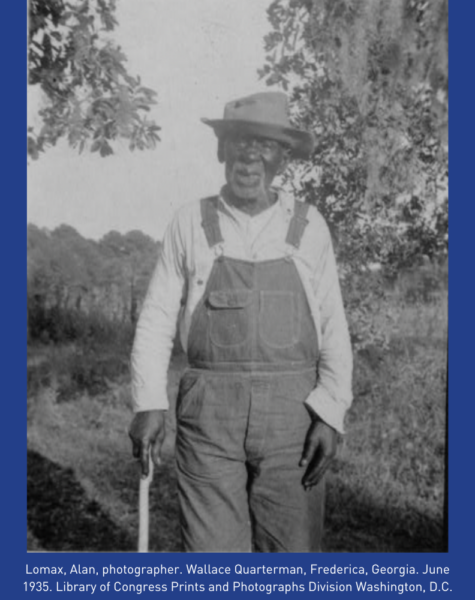

Hunter relied exclusively on written documentation to stake his claim and support his argument, as slavery had already been abolished in both England and the United States by the time recorded sound was invented in 1877. However, you can now listen to interviews with formerly enslaved persons in the Library of Congress’s online presentation Voices Remembering Slavery: Freed People Tell Their Stories. The recordings in this presentation took place between 1932 and 1975 in nine states and are compiled from ten different archival collections held at the Library’s American Folklife Center. Twenty-two interviewees discuss how they felt about slavery, slaveholders, coercion of slaves, their families, and freedom. Several individuals sing songs, many of which were learned during the time of their enslavement.

Additional context and a deeper dive into the history of Handel’s Messiah is now available in a book-length study by historian Charles King. Published in 2024, Every Valley: the desperate lives and troubled times that made Handel’s Messiah has shed new light on the political and social circumstances in which Handel composed this oratorio.

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress documents and shares the many expressions of human experience to inspire, revitalize, and perpetuate living cultural traditions. Designated by the U.S. Congress as the national center for folklife documentation and research, the Center meets its mission by stewarding archival collections, creating public programs, and exchanging knowledge and expertise. The Center’s vision is to encourage diversity of expression and foster community participation in the collective creation of cultural memory.

Despite the word “American” in its title, the American Folklife Center has ethnographical materials in over 500 languages, documenting cultural expression around the world. Learn how to make the most of your visit to the American Folklife Center.

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.