Welcome to the 40th Anniversary Season of National Philharmonic! Last year, NatPhil and the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center formed a partnership to make cultural arts experiences more approachable and accessible. I’m estatic to continue this partnership and serve as your musicological guide in this new season.

Throughout the season, we will explore how pieces of classical music intersect with other forms of expressive culture.

Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape and circumstances. To do that, I will introduce a number of archival resources held at the American Folklife Center, which will help us to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them.

We will dive into the archives, hone our research skills, share our findings, and address any lingering questions. But we’ll have fun, too, as we strengthen our listening skills and enhance your concert experience.

I assure you, regardless of your previous musical experiences or training, the partnership between National Philharmonic and American Folklife Center offers all of us the opportunity to learn – together.

Join me this 40th season of National Philharmonic!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

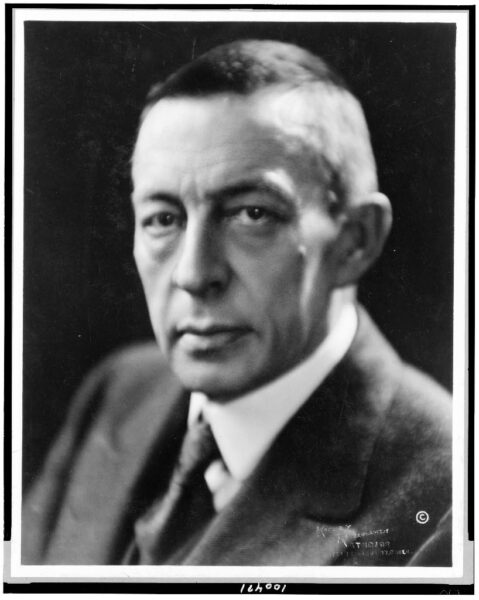

Kubey-Rembrandt Studios, creator. “Sergei Wassilievitch Rachmaninoff, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing left.” 1927. Biographical File filing series – Rachmaninoff, Sergei Wassilievitch, 1873-1943. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90712469/

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) was born near Staraya Russa, which is situated in the northwest corner of Russia. His musical talent was nurtured from a very young age, and he later pursued his formal training in piano and composition at the Moscow Conservatory. While still a student, he wrote the first of his five pieces for piano and orchestra, Concerto No. 1 in F# minor (1891).

After performing extensively in Europe and the United States, Rachmaninoff moved to New York in 1918 during a tumultuous time in Russian history. Today, we know him through his compositions, as several of them have been incorporated (to varying extents) in major motion pictures, such as Groundhog Day (Rhapsody on Theme of Paganini) and Shine (Concerto No. 3 in D minor).

However, during his own lifetime, Rachmaninoff was recognized more for his inimitable artistry at the piano. Indeed, he maintained a very full touring schedule and enjoyed appearing in recitals and with major orchestras, whose programs showcased his own compositions. An intense and dedicated musician, he managed to perform until shortly before his death in 1943, by which time he and his family had relocated to California.

The opening concert of National Philharmonic’s 40th season is unique, as it features three pieces for piano and orchestra—all by Rachmaninoff—written over the course of four decades. He composed his Concerto No. 2 in C minor in installments between 1900 and 1901, and his Concerto No. 3 in D minor was written in 1909. However, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini did not appear until 1934. The composer premiered all three pieces, with the Rhapsody receiving its initial performance by the Philadelphia Orchestra in Baltimore, Maryland.

As you listen to National Philharmonic and each of the pianists, consider the role of composer-as-soloist in each of these works. Be mindful, too, of the similarities and differences within each piece and among the three.

The two concertos each have three movements, and they are arranged in fast-slow-fast order. Even though they share a common structure and instrumentation , the initial moments of each piece exemplify the composer’s wide range of compositional strategies. As an example, the second concerto immediately features the piano in a series of eight thick chords, anchored by a repeated low F. A three-note progression in parallel octaves precedes the entrance of the strings and clarinet, which introduce the main theme against the pianist’s sudden flurry of notes.

The opening theme of the third concerto recalls the melodic contour of the second concerto’s theme, and it is, in its initial statement, deceptively simple. But, the composer’s prowess becomes evident, as what starts out as a haunting melody quickly morphs into a complex web of timbres and textures. In both concertos, however, you’ll be keen to pay particular attention to the ways in which the piano interacts with various wind instruments. And, as the pieces progress, take stock of the lyricism of the second movements and the contrasting energies conveyed in the respective third movements.

Like Concerto No. 3, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini is based on a memorable tune, but unlike other theme-and-variation pieces, the theme in the Rhapsody is presented after the briefest of introductions and first variation. Even so, as the twenty-six-part piece develops, simplicity gives way, and listeners are treated to variation after variation on the theme originally created by composer Niccolò Paganini (1782 – 1840). Rachmaninoff was one of several composers to reconceive this theme, which was originally a caprice for solo violin. As the twenty-fourth of Paganini’s 24 Caprices for Solo Violin (1802 – 1817), it was a real showstopper, because only the most talented of violinists could meet the technical demands of the piece. And, just as his predecessor had done over 100 years prior, Rachmaninoff managed to create a masterpiece from an otherwise unassuming melody.

As the rhapsody unfolds, try to remember which variations resonated with you the most, and why. Were you drawn to the intense fury of notes in the flute, or the sonorous responses to the piano in the double reeds? Did you detect any other familiar tunes? You’ll see (and hear) that the orchestral body mirrors that of the two concertos, but with important additions. Two auxiliary instruments (the piccolo and English horn) expand the range of the upper woodwinds, and the percussion is punctuated by the glockenspiel. How do these instruments add nuance to the orchestra’s sound?

INSTRUMENTATION

Concerto 2: 2 2 2 2 | 4 2 3 1 |perc | str

Concerto 3: 2 2 2 2 | 4 2 3 1 |perc| str

Rhapsody: 2 (+picc) 2 (+ CA) 2 2 | 4 2 3 1 | perc (+glockenspiel)|str (+harp)

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.