Welcome to the 40th Anniversary Season of National Philharmonic! Last year, NatPhil and the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center formed a partnership to make cultural arts experiences more approachable and accessible. I’m estatic to continue this partnership and serve as your musicological guide in this new season.

Throughout the season, we will explore how pieces of classical music intersect with other forms of expressive culture.

Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape and circumstances. To do that, I will introduce a number of archival resources held at the American Folklife Center, which will help us to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them.

We will dive into the archives, hone our research skills, share our findings, and address any lingering questions. But we’ll have fun, too, as we strengthen our listening skills and enhance your concert experience.

I assure you, regardless of your previous musical experiences or training, the partnership between National Philharmonic and American Folklife Center offers all of us the opportunity to learn – together.

Join me this 40th season of National Philharmonic!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

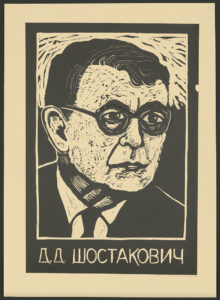

Romero, Rachael, designer. [Dimitrii Shostakovich]. [San Francisco]: Wilfred Owen Brigade, 1976. [print, linoleum cut]. Artist poster filing series, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Indeed, the composer’s career coincided with the rise of the Soviet Union and the dominance of its attendant philosophies, some more consequential than others. At first, Shostakovich found himself aligned with Soviet ideologies and his early works were celebrated. But, as Joseph Stalin’s reign became more dictatorial in 1930s, the government exercised greater scrutiny of its citizens’ artistic output, sometimes issuing warnings and veiled threats that prompted Shostakovich to live in fear for his life.

In spite of this turmoil (or, perhaps, because of it), Shostakovich was remarkably prolific, and his output spanned multiple genres. Among his large-scale works were fifteen symphonies, two concertos each for violin, cello, and piano, numerous orchestra suites, operas, and ballets, in addition to film scores and music to accompany plays. His chamber works included string quartets, solo piano pieces, and a handful of sonatas for solo strings with piano accompaniment and pieces for small ensembles.

Symphony No. 5 is one of the Shostakovich’s most well-known works, having been premiered in 1937 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, just weeks after the composer took up teaching at the conservatory where he had once been a student. Divided into the expected four movements, this symphony thwarts traditional expectations, especially with movements 2 and 3.

Typically, the second movement is slow and lyrical and the third includes a dance rhythm—such as a waltz, scherzo, minuet, etc. But in the case of Symphony No. 5, the roles of those two movements are reversed. Listeners will be treated to other surprises, as well, especially considering how the auxiliary percussion and wind instruments transform the resultant soundscape.

Unlike the symphonies of previous eras, this one (like many of its contemporaries) offers twists and turns that are challenging to describe without the aid of musical notation or sound bytes. Even so, as the work unfolds over time, audience members will discern major, and sometimes very abrupt, tonal, melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, and textural changes, both within a movement and among movements. Listeners can leverage such changes to consider the music’s more qualitative features—most notably, the emotions it evokes and the energy it generates. Pay particular attention to how each movement begins and ends, and then reflect on the overarching narrative(s) of the piece as a whole.

Can you identify these five events within the piece?

Symphony No. 5 received its American premiere on April 9, 1938. By using the Library of Congress’s database of newspapers, Chronicling America, you can learn more about the composer’s first two (of three) trips to the United States and investigate the American reception of Shostakovich’s music until 1963, when coverage for Chronicling America stops.

The Library of Congress has several resources related to Dmitri Shostakovich. Feel free to stop by the American Folklife Center exhibit before or after the concert and during intermission to learn more.

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.