Over the course of the season, we will explore how each of the pieces operates at the intersection of classical and folk musics. In each instance, we will start with a classical construct–that is, a concerto, a symphony, a solo piano piece, and the like–and we will investigate how and to what extent folk idioms are infused into each construct. Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape comprising all the musics with which he or she was familiar. To do that, I will introduce a number of primary (archival) resources that can be used to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them beyond what has been the subject of musical biographies and histories. Many of these primary resources are available at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, but I will include others to facilitate our efforts. Some of them can be consulted online, while others may be used onsite at the Library. But all of them, singly and collectively, document the variety of cultural expressions and lived experiences that have been, in some way, referenced by the composers in their works.

On this site, you will find links to manuscripts, unique images, archival repositories and their finding aids, sound recordings, and more. Explore as much as your time permits. Start with the four “quantitative interrogatives”: who? what? when? where?

Use these questions to guide your examination of the resources, individually and in combination with each other. Then, leverage your new (or nuanced) understanding of a particular folk idiom–a dance, a concept, a tune, a rhythm–to expand your knowledge of the piece in which this idiom appears.

Before and after each concert, we will have opportunities to discover new resources, hone our research skills, discuss our findings, and address any lingering questions. With each exchange of ideas comes the opportunity for discovery. May this be the beginning of an exciting musical journey—for all of us!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

Breaths of Universal Longings, by James Lee III, was commissioned by The May Festival of Cincinnati as part of the organization’s 150th anniversary celebration taking place this year—making it the oldest choral festival in the western hemisphere. And tonight, we have the distinct honor of witnessing the piece’s East Coast Premiere. Scored for chorus, youth chorus, and orchestra, Breaths of Universal Longings divides into four movements.

Breaths of Universal Longings, by James Lee III, was commissioned by The May Festival of Cincinnati as part of the organization’s 150th anniversary celebration taking place this year—making it the oldest choral festival in the western hemisphere. And tonight, we have the distinct honor of witnessing the piece’s East Coast Premiere. Scored for chorus, youth chorus, and orchestra, Breaths of Universal Longings divides into four movements.

The first movement, titled “From Dust We Were Made,” is derived from Genesis 2:7, which recounts God’s formation of living souls from the dust of the ground.

“And the LORD God formed man the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”

(Genesis 2:7 KJV)

Lee then draws from Job 38:7, which emphasizes the singing and shouting for joy.

“When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

(Job 38:7 KJV)

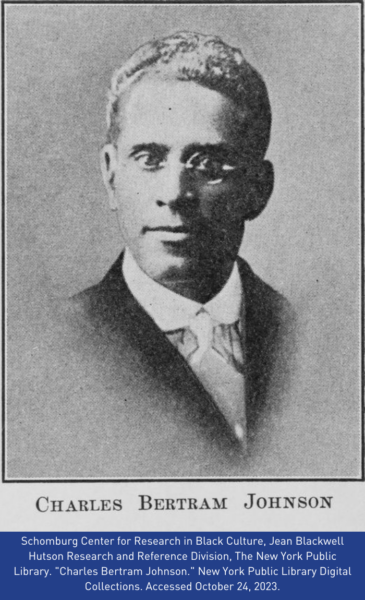

The notion of song is evident in the second movement, titled “Now and Then,” which features text from Charles Bertram Johnson’s poem of the same name. Johnson (1880-1958), a native of Missouri, spent his formative years hearing his mother rhyming. His exposure to literature spanned the gamut—ranging from William Shakespeare to Library of Congress employee Paul Lawrence Dunbar, the latter serving as inspiration for Johnson’s 1918 poem “Mantle of Dunbar.” That same year, Bertram published an anthology of poetry titled Songs of My People, which includes the poem “Now and Then.”

Song is a theme in Johnson’s poetry from this period. For example, in 1919, his poem “Soul and Star” appeared in The Crisis, which had established by W.E.B. Du Bois as the official publication of the NAACP.

Two years later, The Crisis published Johnson’s “A Song of Hope.”

In his 1923 publication Negro Poets and their Poems, author Robert T. Kerlin reflected on Johnson’s style. “ . . . [a] lyric poet should sing himself. That is the essence of lyric poetry. In so singing, however, the poet reveals not only his individual life, but that of his race to the view of the world.”

In the third movement “Reflection,” Lee set texts written by members of the May Festival Youth Chorus, and these texts convey sentiments of joy, singing, longing, and belonging. According to Lee, both his music and their texts were created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent interview with Eugene Rogers, Lee mentioned that the choristers were completely unaware of Lee’s other textual selections. As such, Lee was interested to discover that, in their submission, the very first line reads “Where is the Song?”

The piece concludes with the final movement titled “Seeking Joy,” which sets the text of William Henry Davies’s poem by the same name. Davies (1871-1940), spent much of his life traveling and living the life of a hobo. A native of Wales, Davies meandered through the United Kingdom and the United States, and his writings reflected his lived experiences. The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp (1908; later editions), Beggars (1909), and The True Traveller (1912), and A Poet’s Pilgrimage (1918), and Later Days (1925) were among his reflective writings. Meanwhile, he also issued several collections of poetry, including Foliage: Various Poems (1913), in which “Seeking Joy” was printed.

Another poem from this collection, “Night Wanderers,” was among three of Davies’s works to have been set to music by composer Samuel Barber.

In Breaths of Universal Longings, Lee employs texts, which emerged under vastly different circumstances, to convey the essence of life and the role of song in imbuing life with meaning. In their own ways, each of the texts captures a part of the human experience, which, in turn, gives rise to a unique continuity over the four-movement work.

Antonio Estévez (1916-1988) was born in Venezuela and showed musical promise at a young age, playing the saxophone and later pursuing serious studies of the oboe and composition. In his most well-known piece, Cantata Criolla: Florentino el que cantó con el Diablo (Florentino, the one who sang with the Devil), Estévez set a story from Venezuelan folklore that had been rendered in poetic form by the Venezuelan writer Alberto Arvelo Torrealba (1905-1971). In the story, Florentino is a coplero—a singer who improvises on short lines—and he faces the Devil in a singing contest.

Antonio Estévez (1916-1988) was born in Venezuela and showed musical promise at a young age, playing the saxophone and later pursuing serious studies of the oboe and composition. In his most well-known piece, Cantata Criolla: Florentino el que cantó con el Diablo (Florentino, the one who sang with the Devil), Estévez set a story from Venezuelan folklore that had been rendered in poetic form by the Venezuelan writer Alberto Arvelo Torrealba (1905-1971). In the story, Florentino is a coplero—a singer who improvises on short lines—and he faces the Devil in a singing contest.

The piece, dating from 1954, is scored for orchestra, chorus, and two soloists in three large-scale movements. In the first movement “El Reto” (“The Challenge”), the chorus introduces Florentino, characterizing him as lonely, dirty from his time travelling outdoors, and very, very thirsty. Florentino rides his horse to the edge of a pond, where he is desperate to get some water. But each time he tries to fill his water bottle, he only retrieves sand. He hears another horse approach from behind, on top of which sits a figure dressed all in black—the Devil. The Devil challenges Florentino to a duel of song in Santa Inés, which is in the northwestern part of Venezuela. After issuing the challenge, the Devil takes off, accompanied by cowboys. In contrast, Florentino travels to Santa Inés alone, expressing that he will rise to the Devil’s challenge, not because he wants to, but because he must live up to the expectations of a coplero.

The chorus returns in the second movement “La Porfía” (“The Duel”) to narrate the arrival of the Devil at Santa Inés prior to the duel. The choir immediately shifts from singing to speaking in a manner devoid of tonality, which has long been used as a compositional strategy for representing the Devil.

The third movement features the duel, with Florentino and the Devil exchanging musical taunts. Halfway through, the Devil concedes that Florentino sings well but only because Florentino had made a pact with him. This reference to the legend of Faust is poignant, and it is countered by Florentino, who closes the duel with multiple references to religious figures.

Estévez employed several folk idioms in Cantata Criolla, most notably, the joropo* rhythm, circum-Caribbean** polyrhythms***, and percussive gestures to imitate or indicate movement (especially that of horses). Joropo is a music-and-dance genre that originated in Venezuela, and its rhythm, at its most fundamental, is built from a strong feel of three beats, as follows: 1 x 3 ||1 x 3 ||1 x 3

Certainly, Cantata Criolla includes permutations of this rhythm, featuring different subdivisions and emphases, all of which lend the piece a sense of momentum and even playfulness. Estévez does not limit his idiomatic writing to rhythm; in fact, much of his melodic and harmonic writing is designed to suggest the places, topics, and concepts mentioned in the text. For example, big, brassy chords convey the vast swath of land over which Florentino traverses. And, in acknowledgement of the predominantly Catholic population in Venezuela, Estévez infuses two well-known (and regularly quoted) chants into his piece: Ave maris stella for Florentino and Dies irae for the Devil. The medieval chant Ave maris stella (Hail, star of the sea) is typically sung at Vespers (evening prayer service of the Catholic Church) and portrays Mary as a forgiving and loving Mother. Dies irae (Day of wrath) is used in the Requiem Mass (Mass for the dead).

By selecting and pairing these two chants, Estévez demonstrated his own understanding of how certain Catholic chants, once reserved for specific religious services, have become incorporated into more mainstream (and even popular) discourse.

[*joropo = the national ballroom dance of Venezuela]

[**circum-Caribbean = the land near and around the Caribbean Sea]

[***polyrhythms = the presence of more than one rhythm at the same time]

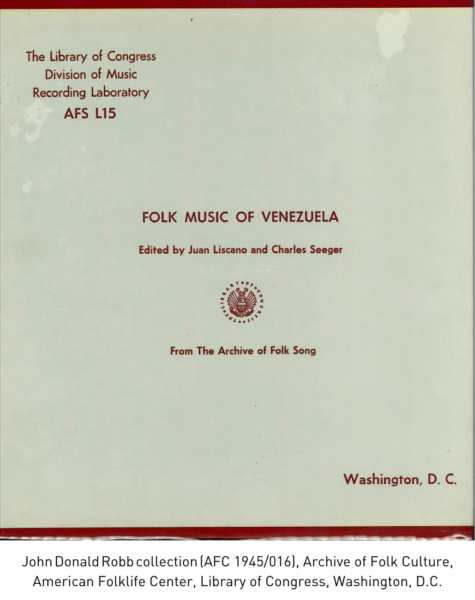

To hear more music from Venezuela, come to the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress to explore the archival collections. Despite the word “American” in its title, the American Folklife Center has ethnographical materials in over 500 languages, documenting cultural expression around the world. Learn how to make the most of your visit to the American Folklife Center.

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.