Over the course of the season, we will explore how each of the pieces operates at the intersection of classical and folk musics. In each instance, we will start with a classical construct–that is, a concerto, a symphony, a solo piano piece, and the like–and we will investigate how and to what extent folk idioms are infused into each construct. Together, we will consider each piece as a function of the composer’s unique soundscape comprising all the musics with which he or she was familiar. To do that, I will introduce a number of primary (archival) resources that can be used to contextualize these pieces and nuance our understanding of them beyond what has been the subject of musical biographies and histories. Many of these primary resources are available at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, but I will include others to facilitate our efforts. Some of them can be consulted online, while others may be used onsite at the Library. But all of them, singly and collectively, document the variety of cultural expressions and lived experiences that have been, in some way, referenced by the composers in their works.

On this site, you will find links to manuscripts, unique images, archival repositories and their finding aids, sound recordings, and more. Explore as much as your time permits. Start with the four “quantitative interrogatives”: who? what? when? where?

Use these questions to guide your examination of the resources, individually and in combination with each other. Then, leverage your new (or nuanced) understanding of a particular folk idiom–a dance, a concept, a tune, a rhythm–to expand your knowledge of the piece in which this idiom appears.

Before and after each concert, we will have opportunities to discover new resources, hone our research skills, discuss our findings, and address any lingering questions. With each exchange of ideas comes the opportunity for discovery. May this be the beginning of an exciting musical journey—for all of us!

— Dr. Melanie Zeck

Bain News Service, publisher. Lili Boulanger. 1918 (date created or published later by Bain). Photograph. Bain News Service photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014708112/.

Marie-Juliette Olga “Lili” Boulanger (1893 – 1918) was born in Paris, France, into a family of musicians across three generations, several of whom studied and/or taught at the Paris Conservatory. Her musical aptitude was recognized when she was only a toddler, and despite being plagued by illness throughout her short life, she was a well-rounded and remarkably successful musician. As the first woman to win the coveted Prix de Rome for composition in 1913, she followed in the footsteps of her father Ernest, who had won the prize in 1835.

Scored for brass ensemble (4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones, 1 tuba), timpani, 2 harps, organ, and choir, Psalm 24 “La Terre Appartient à L’éternel” was written in 1916. In the Bible, Psalm 24 [KJV] declares that “the earth is the Lord’s, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein.” It goes on to describe the characteristics of someone likely to “ascend into the hill of the Lord.” Although Psalm 24 may not be as well-known as its immediate predecessor (Psalm 23, “The Lord is My Shephard, I shall not want”), Boulanger created a musically memorable setting of it.

The brass ensemble presents a fanfare reminiscent of grand pronouncments and royal events, especially in conjunction with the timpani. The organ complements the brass and timpani, referencing both its presence in traditional worship services and its emergence as a powerful instrument in nineteenth-century France.

Boulanger’s use of French (as opposed to Latin) is also noteworthy, especially during the First World War, when nationalistic fervor was high. Her wartime activities—including her compositions and charity work—were recently the subject of a scholarly study by Anya B. Holland-Barry. Barry investigates the presence of wartime themes, such as suffering and sadness, in Boulanger’s writing, and she implies that the composer’s musical output portended an inimitable career that was sadly cut short.

Ultimately, you may decide to consider Boulanger’s Psalm 24 as a powerful contrast to her perpetual frail state and the political turmoil around her. To contextualize her efforts further, visit the Library of Congress Veterans History Project online collections and explore them through the digital discovery tools. Each of the featured World War I Correspondence Collections includes first-person accounts of American military personnel who served in France.

Siegel, Adrien, photographer. [Igor Stravinsky, 1882 -1971, half-length portrait, winding watch]. No date. Photograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/2005691540/.

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882 – 1971) was born Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov, St. Petersburg, Russia). His father was a professional opera singer, and the younger Stravinsky followed suit, pursuing his own musical studies (piano, theory) throughout his childhood. Enthralled by a performance Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty, Stravinsky would go on to compose ballets of his own, many of which are still in circulation (as the fully produced ballet or as orchestral concert works [without dancing]): L’Oiseau de feu (The Firebird, 1910), Pétrouchka (Petrushka, 1911) Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913), among others.

By the time Stravinsky composed the Symphony of Psalms in 1930, he had already been living abroad (first in Switzerland and then in France) for fifteen years because it had become too difficult to earn a living as a composer in his homeland. Russia’s political and economic state had been adversely affected by the First World War and the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Each of the three movements features a psalm text and a large, but unconventional, orchestra. Movement 1 employs Psalm 39:12-13, Movement 2 is a setting of Psalm 40:1-3, and Movement 3 features Psalm 150. It should be noted that Stravinsky used The Vulgate, which is the Latin version of the Bible that assigns these Psalms the following numbers: Psalm 38, Psalm 39, and Psalm 150 respectively. Scored for 5 flutes (including one doubling on piccolo), 4 oboes, 1 English horn, 3 bassoons, 1 contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 1 piccolo trumpet, 3 trombones, 1 tuba, percussion, 2 pianos, harp, cellos, basses, and chorus, the piece noticeably excludes any clarinets, violins, or violas.

Much later in life, Stravinsky discussed his compositional process at great length with his long-time assistant and friend, Robert Craft. The Library of Congress’s Music Division holds the Robert Craft collection on Igor Stravinsky, 1912 – 1966, whose contents are listed here. Their conversations were ultimately published in monographs aptly titled Memories and Commentaries (1958), Conversations with Igor Stravinsky (1959) and Dialogues (1982, which served as a revised version of Dialogues and a Diary (1963, 1968). In one such dialogue, Craft posed several questions to Stravinsky about Symphony of Psalms, which had been commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Stravinsky replied:

The first movement, ‘Hear my prayer, O Lord,’ [Psalm 39: 12-13; Vulg. Psalm 38: 13-14] was composed in a state of religious ebullition. The sequences of two minor thirds joined by a major third, the root idea of the whole symphony, were derived from the trumpet-harp motive at the beginning of the allegro in Psalm 150. . . .

The ‘Waiting for the Lord’ Psalm [Psalm 40: 1-3; Vulg. Psalm 39: 2-4] makes the most overt use of music symbolisim in any of my music before The Flood [a musical play written in 1962]. An upside-down pyramid of fugues, it begins with a purely instrumental fuge of limited compass and employs only solo instruments. . . . The next and higher stage of the upside-down pyramid is the human fugue, which does not begin without instrumental help . . . but the human choir is heard a capella [without instrumentation] after that. The human fugue also represents a higher level in the architectural symbolism by the fact that it expands into the bass register. The third stage, the upside down foundation, unites the two fugues. . . .”

Commenting on the last movement, the composer notes:

Here is an excerpt from the third movement (first in Latin and then in English, with relevant words bolded). As you listen to the music, consider the Stravinsky’s admission of having written something “so literal.”

Praise Him in the sound of the trumpet.

Praise Him with timbrel and dance.

Praise Him with strings and organ.

Praise Him with on high sounding cymbals.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) was born in Germany and, as a boy, he began studying the piano with his father. The life, career, music, and reception of the younger Beethoven have been thoroughly documented, but his personal circumstances, especially his ability to compose after having lost his hearing, have made him the subject of continued intrigue.

Beethoven was prolific, and he was also a visionary who ushered in the Romantic era of music in the early nineteenth century. His own compositional style can be broken down into three phases, with the first anchored squarely in the Classical era, whose other figures include Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809) and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791). Like his contemporaries, Beethoven was able to compose successfully across a number of genres—

His trajectory and musical maturation can be measured within each genre and across his entire output, which culminated in his Symphony No. 9 scored for orchestra, chorus, and soloiosts (premiered in 1824). Although this was his first (and only) symphony to combine such robust forces, Beethoven had been creating large-scale works featuring an orchestra and chorus since the second phase of his career. For example, his Mass in C Major, Op. 86 was commissioned in 1807 by Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, whose family had also employed Haydn, and it was premiered that year by the Prince’s musicians. The following year, Beethoven conducted excerpts from the mass at a concert in Vienna, which also marked the premieres of his Symphony No. 5 and Symphony No. 6 “The Pastoral.” Recall that National Philharmonic performed Symphony No. 6 at its season opener in October 2023.

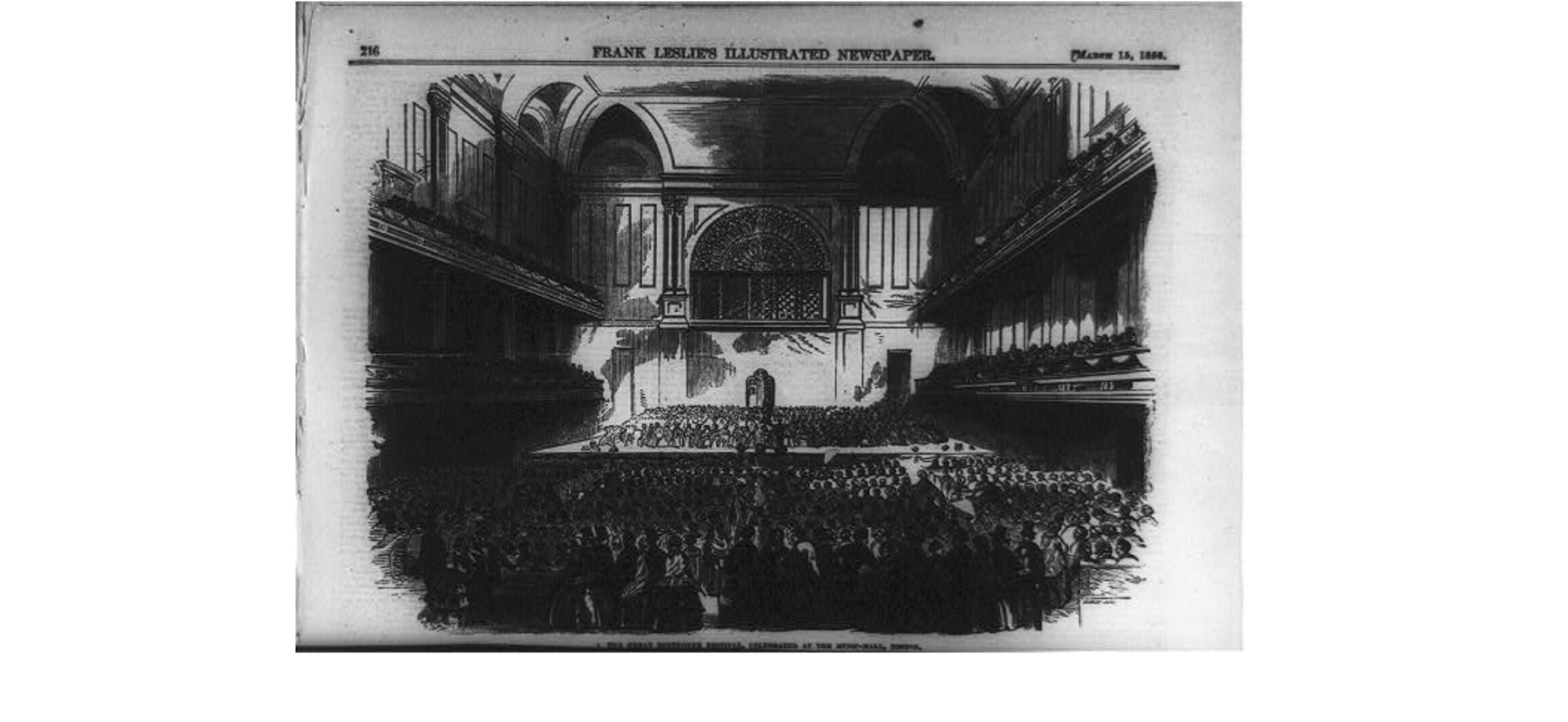

The great Beethoven Festival, celebrated at the Music-Hall, Boston interior, during performance, 1856. Wood engraving, image printed in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper 1, no. 14 (March 15, 1856), p. 216

In a mass, there are two parts: the Ordinary and the Proper. The components of the Ordinary do not typically vary—that is, the Ordinary remains the same throughout the Liturgical year. Its components are:

Kyrie (Lord Have Mercy)

Gloria (Glory to God in the Highest)

Credo (I Believe in one God)

Sanctus (Holy, Holy, Holy)

Agnus Dei (Lamb of God)

Ite, missa est (Go, it is the dismissal)

Musical settings of a mass may include a Benedictus with the Sanctus, and there may be no Ite, Missa Est. The Proper of the Mass is designed to align with the specific day of the Liturgical calendar. Components of the Proper include the Introit, Gradual, Alleluia / Tract, Sequence, Offertory, and Communion.

Beethoven’s five-movement mass includes the five components of the Ordinary. The piece is scored for pairs of each woodwind, French horn, and trumpet, in addition to timpani, strings (violins 1 and 2, violas, cellos, basses), organ, 4 vocal soloists, and chorus.

In the first movement, you will hear only two phrases: Kyrie Eleison (Lord Have Mercy) and Christe Eleison (Christ Have Mercy), with a return of Kyrie Eleison. Some key things to listen for:

In the second movement, you will immediately be struck by a fortissimo (very loud) entrance of the entire orchestra and chorus, which announces “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” (Glory to God in the Highest). As the orchestra thins out, you will hear Beethoven’s more syllabic writing—that is, each syllable of the text is rendered with a single pitch—thereby contrasting with the melismatic writing found in the first movement. The chorus tends to sing homophonically in this movement, with all four sets of voices (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) moving at the same time. Toward the end of the movement, a different style of polyphony (presentation of multiple parts simultaneously) prevails, with staggered entrances in the chorus and among the soloists. The movement concludes with a resounding “Amen.” Throughout the movement, be mindful of the role that each of the woodwinds plays in supporting the vocalists.

The third movement Credo opens with an arpeggio-like figure in bassoons and low strings, to which the higher strings respond with the same figure. Interspersed is a homophonic statement of “Credo” in the chorus. How does this movement compare to the previous two? Take a look at the lyrics to this movement. Where does Beethoven employ homophonic writing? When does he used staggered polyphony? Does this movement offer repeated phrases (like in the first movement), or does it continue to evolve?

The woodwinds and lower strings (including the viola) introduce the fourth movement (Sanctus) of the mass, and the chorus presents its opening statement homophonically. As the movement unfolds, how would you characterize the melodic contours of the woodwinds and strings? Are they stagnant? More virtuosic? How do they resemble or counter the contours of the soloists?

In the final movement (Agnus Dei), turn your attention to the brass and the clarinets. How to they accentuate the performance? Listen, once again, for the types of harmony you are hearing–homophony and polyphony. What is different about this particular movement, compared to the previous four? As you recall each of the five movements, how would you characterize them—singly and collectively?

Prince Nikolaus Esterházy did not respond to Mass in C Major, Op. 86, as favorably as Beethoven would have liked. The piece was not published for another five years, and it was, eventually, overshadowed by the composer’s more famous Missa Solemnis (1823).

What do you think? If you were in National Philharmonic’s audience in October, you will now be able to compare Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 with Mass in C Major and think more critically about how the composer conveyed meaning in both pieces. And, if you’ve attended additional concerts this season (and skimmed the program annotations), you will, no doubt, recognize the extent to which you have expanded your musical vocabulary. How would you compare Beethoven’s style to those of the other composers you have heard?

National Philharmonic relies on the generosity of its donors to continue bringing you the music. Your contribution is critical to our continued success.